Pachamama Meaning In Andean Culture

James Bustamante is Native to New York but born to Peruvian parents. He has been traveling throughout Latin America since early 2003 and finally made his home in Peru. James has made his way by eating and traveling through almost every country in Central and South America.

Last Updated on December 13, 2023 by James Bustamante

One of Peru’s most ancient and revered customs is the offering to Pachamama, also spelled Pacha Mama. This ritual remains a vital part of the Peruvian spiritual practice in the Andes mountains. This ritual is a significant cultural experience and one of the most fascinating activities for visitors to Peru.

To enhance your understanding and appreciation of this revered female Andean deity, we have compiled a concise guide in collaboration with the travel specialists at Journey Machu Picchu. This guide aims to familiarize you with the various rituals you might encounter near Peru’s major attractions, ensuring your visit is enlightening and unforgettable.

What is The Meaning of The Word Pachamama?

The term ‘Pachamama’ holds a significant place in the hearts and minds of the Peruvian people. But what exactly does this term mean? In the era of the Incas, Quechua was the lingua franca. From this ancient language comes the word Pachamama, with ‘Pacha’ translating to ‘universe,’ ‘world,’ or more commonly, ‘earth,’ and ‘Mama’ meaning ‘Mother.’ Therefore, Pachamama can be understood as ‘Mother Earth,’ a nurturing, life-giving entity central to the Andean worldview.

Pachamama is more than a mere mythological figure; she represents the interconnectedness of all living things and the interchange between humans and the natural world. Pachamama is revered and respected in the Andean belief system, with rituals and offerings to ensure harmony and balance within the environment.

As a travel professional, I recommend that those choosing a Peru travel package immerse themselves in the local culture by learning about Pachamama. This understanding not only enriches the travel experience but also fosters a deeper connection with the breathtaking landscapes you will encounter, from the majestic Andes to the verdant Amazon rainforest. Experiencing Peru through the lens of Pachamama adds spiritual and cultural depth to your journey, allowing for a more meaningful and memorable exploration.

Understanding Pachamama also provides context to many of the customs, festivals, and daily practices you will observe in Peru. It’s a concept that permeates many aspects of Peruvian life, influencing art, agriculture, and community practices. Engaging with this aspect of Peruvian culture offers a unique perspective on how ancient traditions continue influencing modern life in Peru.

An Introduction to The Pachamama

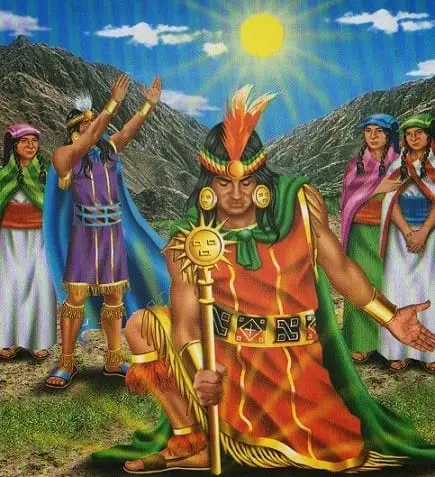

Pachamama, a revered ancient female deity, holds a special place in the hearts of the Andean and Amazonian people of Peru and other parts of South America as well. According to local scholars, she embodies “Mother Earth,” providing her children sustenance, support, and protection. In current times, particularly in the Andes, she is honored with offerings during planting and harvesting seasons, believed to inhabit mountains, and associated with causing earthquakes and influencing fertility.

For the Incas, before the Spanish arrival, Pachamama was more than just Mother Earth; she symbolized the essence of nature and the life cycle it encompasses. This deity was central to the fertility of the people, the growth and harvesting of crops, and represented the earth’s generosity and abundance. She was revered for using her bountiful produce to safeguard her worshippers, linking her closely to agricultural productivity.

Today, the veneration of Pachamama remains vibrant and relevant despite the evolution of religious practices and the growing influence of Catholicism.

The belief in this deity continues to be a significant aspect of the cultural fabric, especially in Andean cities like Cusco. The worship and adoration of Pachamama persist, reflecting a deep-rooted respect for the environment and the ancestral traditions that have shaped these communities. This enduring reverence highlights the ongoing cultural synthesis and the resilience of ancient beliefs in the modern world.

Pachamana and The Incas

While the Sun god Inti was revered as the principal deity in Inca cosmology, the importance of other gods, particularly the Andean Mother Earth, escalated over time, especially after the Spanish conquest. It’s crucial to remember that the Inca civilization was an amalgamation of various pre-Inca cultures, human settlements, and small villages scattered across Tawantinsuyo before the 13th century. These distinct groups had their deities and unique worship practices.

The Incas absorbed several of these gods through conquests and unions into their pantheon. For example, the Sun god, initially worshipped by the Tiahuanaco pre-Inca culture, and the supreme deity Viracocha, revered as the creator by the Caral culture and subsequently by the Chavin, Wari, and Tiahuanaco cultures, were adopted into the Inca religion. However, the gradual overshadowing of Viracocha by the more tangible and daily presence of the Sun remains a historical enigma.

Despite these evolutions in worship, embodying the female essence of nature, the Andean Mother Earth retained her significance throughout and beyond the Incan period. She was revered as the provider of life, food, animals, and water and was linked to various atmospheric and geological phenomena, playing a pivotal role in Peru’s rich biodiversity. Her importance was further underscored by the fact that the Inca economy was predominantly agricultural, making her veneration crucial for the prosperity and sustenance of their culture.

The Andean Mother Earth was believed to be fertilized by the rain, and the Sun God and was seen as the source of bountiful harvests. This relationship highlights the intricate and harmonious balance perceived by the Incas between different natural elements and their deities. Her continued reverence, surviving the shifts brought by the Incas and later the Spanish conquest, is a testament to her enduring legacy as a fundamental and life-giving force in the Andean worldview.

The Belief of Duality and The Incas

In the Inca’s way of life, the principle of duality stood as a cornerstone of their worldview. This concept was deeply ingrained in their understanding of the universe, where every entity or element had a complementary counterpart, reflecting a balance essential to their belief system. This duality extended to their practices of tribute and sacrifice, where offerings typically involved pairs, such as two animals, one male and one female, to appease and garner favor from the gods. Being favored by the gods meant a good harvest, which meant food security for the season.

Each deity in the Inca pantheon had its counterpart, exemplifying this concept of duality. The Andean Mother Earth, or Pachamama, was paired with Inti, the Sun god, signifying the interdependence between the Earth and the Sun. Similarly, water and fire were considered complementary forces, as were the Kay Pacha (the earthly realm) and Hanna Pacha (the heavenly realm). These pairings were not merely symbolic representations but were integral to the Inca understanding of balance and harmony in the natural world.

It is crucial to note that this concept of duality in Inca belief should not be mistaken for the dichotomy of good and evil, as understood in many other cultures. The Incas perceived their deities as complex beings capable of benevolence and wrath. In their worldview, the qualities of mercy and punishment, or good and evil, were not mutually exclusive but could coexist within a single deity. This perspective highlights the nuanced and sophisticated nature of Inca theology, where gods were seen as multifaceted entities embodying the diverse aspects of existence and the natural world.

This duality principle is a fascinating aspect of Inca culture, offering insight into their perception of the universe and their place within it. It underscores the complexity and depth of their religious beliefs, where harmony and balance were paramount, and every element of the natural world was interconnected and interdependent.

Reciprocity and The Incas

The Incas, renowned for their sophisticated culture and beliefs, practiced a unique form of reciprocity in their offerings, or ‘Challa’ in Quechua, to the Andean Pachamama. This reciprocal relationship between the people and the divine was a central tenet of their worldview, exemplifying a deep connection with the natural and spiritual realms.

The offerings made to Pachamama were rich and symbolic, comprising packages filled with an array of natural produce. These included dry coca leaves, fresh fruits, corn, and Andean cereals such as Kiwicha and Quinoa. These items were not chosen randomly; they were the products the goddess bestowed upon them, embodying the principle of “you give me, and I give you.” This ritual was a tangible expression of gratitude and balance between humans and the earth, a cycle of giving and receiving that underscored the harmony the Incas sought to maintain with nature.

These offerings were carefully placed in specific sacred locations called ‘Huacas.’ Huacas were not ordinary places; they were caves, mountains, or rocks, often resembling animals or holding other significant forms imbued with spiritual significance. By burying these offerings in the Huacas, the Andean people symbolically returned to Pachamama what she had provided them, especially during the harvest times.

This practice of making offerings to Pachamama was more than a mere ritual; it was a fundamental aspect of Inca life, reflecting a profound understanding and respect for the interconnectedness of all things. It served as a way of expressing gratitude, ensuring balance, and maintaining a symbiotic relationship between humanity and the natural world. The Incas acknowledged their dependence on the earth’s bounty through this ritual. They sought to ensure the continued fertility and productivity of the land, allowing them to reap the fruits of their labor and sustain their communities.

The Andean Pachamama Ceremony

There is a ceremony that takes place and is orchestrated by a traditional shaman. It is called the Pachamama ritual or Pachamama ceremony, which is used to call for good luck in future endeavors. The intricate ritual is detailed below.

Step 1 La Llamada (The Call)

On the eve of the first of August, a date traditionally set aside for offerings to the Andean Mother Earth, a distinctive ritual called “la llamada” takes place in Peru, marking the preparatory phase for the next day’s ceremonies. This ritual involves burning incense and smoke throughout farms, homes, and orchards, serving a dual purpose: to cleanse these spaces of evil spirits and attract positive energy.

Uniquely, this ritual is not limited to spiritual leaders but can be performed by anyone, usually the homeowner or land caretaker, emphasizing its communal and inclusive nature. “La llamada” is not just a ritual act; it symbolizes the deep-seated connection between the physical and spiritual realms, reflecting the community’s ongoing commitment to maintaining a harmonious balance with the natural and spiritual world. For visitors, witnessing “la llamada” offers an insightful window into Peruvian life’s rich cultural and spiritual fabric.

Step 2 Preparing Offerings

At midday, a pivotal moment in the traditional Andean ritual unfolds as Shamans, the esteemed Andean priests, arrive to craft the offerings for Pachamama. These offerings, rich in symbolism and cultural significance, typically consist of:

- coca leaves

- an assortment of fruits

- corn

- wheat

- portions of food prepared for the day

- sweets like candies and chocolate bars

Each element is carefully sprinkled with wine and chicha de Jora, a type of Andean beer made from fermented corn, a beverage that traces its roots back to the times of the Incas.

As the Shaman meticulously prepares the offering, the family gathers around, creating a space of communal reverence and gratitude. During this ceremony, the Shaman thanks the Andean Mother Earth, invoking her blessings for protection and fertility and realizing the family’s intentions and aspirations. This often includes prayers for abundant harvests in the coming season for farming families.

Integral to the ritual is the active participation of each family member. They, too, offer their gratitude to Mother Earth, each making a personal wish while blowing on three coca leaves they have chosen. These leaves, known as ‘Quintu’ in Quechua, are then handed to the Shaman to be included in the offering.

Blowing on the coca leaves and incorporating them into the offering symbolizes a personal connection and individual contributions to the collective prayer, strengthening the bond between the family, the Shaman, and the Pachamama. The ritual, rich in symbolism and communal participation, highlights the deep spiritual connection and respect for nature central to Andean culture.

Step 3 Rituals and Singing

After preparing the offering, the Shaman begins a solitary journey to the nearest Huaca or, a remote, spiritually significant location. This place, often a natural formation like a cave or mountain, is revered in Andean spirituality. Upon arrival, the Shaman begins a sacred process, digging a pit as a gesture of returning the offerings to the earth.

Amidst chanting ritual songs in Quechua and the fragrance of burning incense, the ceremony connects the physical to the spiritual. Chicha de Jora, or wine consumption by the Shaman, is ceremonial and a form of communion with the spiritual realm, enhancing the connection with the Apus, the revered mountain gods.

The ritual culminates with the careful burial of the offering, a profound act of faith and respect towards nature, encapsulating the principles of reciprocity and reverence that are foundational to Andean beliefs. This act fosters a connection with the divine and reaffirms the community’s bond with their natural surroundings and the ancient traditions passed down through generations.

Step 4 Eating With The Family

In the afternoon, the family or whoever asks for the ritual will share lunch with the Shaman as a celebration. This marks the end of the Pachamama ceremony.

Conclusion

The idea of the Pachamama, or Mother Earth as it would be known in English, is still very much alive in Andean cultures as well as with several Amazon rainforest tribes. Many ethnic groups in the highlands still pay tribute to Inti, the Pachamama, and several other deities of the Andes. If you want to know more or take a Peru tour package including a Pachamama ceremony, contact one of our advisors today.